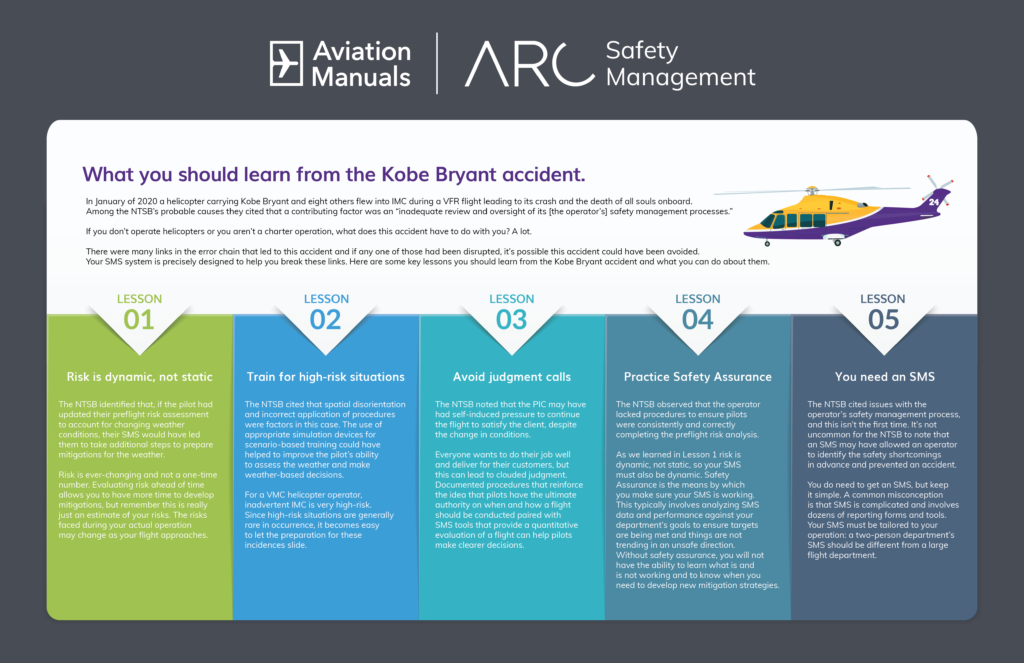

What you should learn from the Kobe Bryant accident

October 4, 2021

In January of 2020 a helicopter carrying Kobe Bryant and eight others flew into IMC during a VFR flight leading to its crash and the death of all souls onboard. Among the NTSB’s probable causes they cited that a contributing factor was an “inadequate review and oversight of its [the operator’s] safety management processes.”

If you don’t operate helicopters or you aren’t a charter operation, what does this accident have to do with you? A lot.

There were many links in the error chain that led to this accident and if any one of those had been disrupted, it’s possible this accident could have been avoided. Your SMS system is precisely designed to help you break these links. Here are some key lessons you should learn from the Kobe Bryant accident and what you can do about them.

Lesson 1: Risk is dynamic, not static

The NTSB identified that, if the pilot had updated their preflight risk assessment to account for changing weather conditions, their SMS would have led them to take additional steps to prepare mitigations for the weather.

Risk is ever-changing and not a one-time number. Evaluating risk ahead of time allows you to have more time to develop mitigations, but remember this is really just an estimate of your risks. The risks faced during your actual operation may change as your flight approaches.

Lesson 2: Train for high-risk situations

The NTSB cited that spatial disorientation and incorrect application of procedures were factors in this case. The use of appropriate simulation devices for scenario-based training could have helped to improve the pilot’s ability to assess the weather and make weather-based decisions.

For a VMC helicopter operator, inadvertent IMC is very high-risk. Since high-risk situations are generally rare in occurrence, it becomes easy to let the preparation for these incidences slide.

Lesson 3: Avoid judgment calls

The NTSB noted that the PIC may have had self-induced pressure to continue the flight to satisfy the client, despite the change in conditions.

Everyone wants to do their job well and deliver for their customers, but this can lead to clouded judgment. Documented procedures that reinforce the idea that pilots have the ultimate authority on when and how a flight should be conducted paired with SMS tools that provide a quantitative evaluation of a flight can help pilots make clearer decisions.

Lesson 4: Practice Safety Assurance

The NTSB observed that the operator lacked procedures to ensure pilots were consistently and correctly completing the preflight risk analysis.

As we learned in Lesson 1 risk is dynamic, not static, so your SMS must also be dynamic. Safety Assurance is the means by which you make sure your SMS is working. This typically involves analyzing SMS data and performance against your department’s goals to ensure targets are being met and things are not trending in an unsafe direction. Without safety assurance, you will not have the ability to learn what is and is not working and to know when you need to develop new mitigation strategies.

Lesson 5: You need an SMS

The NTSB cited issues with the operator’s safety management process, and this isn’t the first time. It’s not uncommon for the NTSB to note that an SMS may have allowed an operator to identify the safety shortcomings in advance and prevented an accident.

You do need to get an SMS, but keep it simple. A common misconception is that SMS is complicated and involves dozens of reporting forms and tools. Your SMS must be tailored to your operation: a two-person department’s SMS should be different from a large flight department.

Log in to ARC for the full guide with extra tips on what you should be doing to address the lessons learned.